Tuesday September 16, 2014

How To Reduce Taxes Using Exchange Traded Funds

You Can’t Control The Stock Market, But You Can Influence The Taxes You Pay On Investments

Ok sort of… The reality is there’s very little you can control when investing, but you can definitely influence a few important things. One strategy you have control over is what investments you use to manage your taxes. This post will focus exclusively on how using exchange traded funds (ETFs) versus mutual funds can help lower your current tax bill, especially capital gains tax. For any of the following to matter, it helps if you are in a tax bracket that actually taxes investment dividends, interest, and capital gains. Let’s begin with an overview of tax rates and brackets. In 2014, a married filing jointly taxpayer earning less than $73,800 will reside in the 15% tax bracket. If you’re a single taxpayer, your number is $36,900. If you think you’ll fly under these thresholds, then stop reading now since none of this applies to you as you’ll pay 0% tax on investment capital gains, dividends, and interest. Wait, there’s more tax jargon we have to pay attention to first… If you end up with a Modified Adjusted Gross Income of more than $250,000 in 2014, then you’ll likely have to pay an additional 3.8% in addition to your 15% capital gains rate. This extra 3.8% is called Net Investment Income Tax, and it’s levied to help pay for the subsidies available within the Affordable Care Act. If you are married filing jointly and end up in the top tax bracket (making over $457,601), then you’ll pay a capital gains rate of 20% plus the additional 3.8%. Next, we have to understand whether or not ETF dividends are qualified (underlying shares in the ETF held by the ETF for more than 60 days) or non-qualified dividends (those that don’t qualify for qualified status, duh). Most domestic ETFs are structured so that the dividends they pay out to shareholders are qualified, and if you’re married filing jointly making between $73,800 and $457,601, you’ll pay 15% on qualified dividends. Remember that if you’re married filing jointly and have a Modified Adjusted Gross Income over $250,000, you’ll pay that pesky 3.8% Net Investment Income Tax on top of the 15%. Last, we have to account for dividends that bond ETFs pay. These dividends ultimately come from the bond’s interest income within the ETF, and although its called a dividend, it’s technically taxed as interest and ordinary income tax rates apply.

Let’s Examine The Capital Gains Scenarios Between An ETF Investor Versus A Mutual Fund Investor

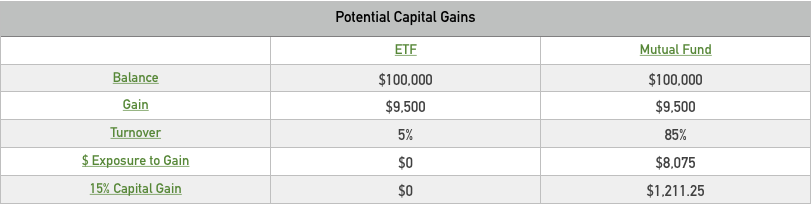

One investor holds $100,000 in a stock based mutual fund and the other holds $100,000 in a stock based ETF. Let’s assume the mutual fund is similar to the ETF in holdings, and therefore the dividends and interest are the same. However, an ETF investor can come out significantly ahead of the mutual fund on the amount of internal capital gains the funds pass onto to investors. This fund mechanic is called “turnover”. Fund turnover can be defined as the total amount of new stocks bought, or amount of stocks sold (whichever is less), over a 12 month period divided by the share price of the fund. Let’s assume both investors are married filing jointly and have a Modified Adjusted Gross Income of $200,000 (15% long term capital gains rates apply with no other IRS tax monkey business). We’ll also assume the mutual fund manager has a turnover percentage of 0.85% since this is probably close to the average. I’ll use the ETF ticker symbol (IVV) and it’s turnover of 5% as a comparison. Although a few of the stocks making up the index are swapped out each year, an investor has not seen a long or short term capital gain distribution because the small amount of capital gains resulting from sells within the ETF and its underlying index were passed onto the investor as dividend income. Last, we’ll assume each investment returned 9.5% (average stock return since 1928) last year. Check out the difference in the capital gains tax liability passed on to the investor:

So in this example representing the averages, the investor ended up paying an extra $1,211 in capital gain taxes just by owning an actively managed mutual fund. The investor didn’t even sell any of the fund, yet they still got clobbered with capital gains! I even did the mutual fund in the example a favor by assuming 100% of the capital gains were long term (15% tax rate), versus short term (ordinary income tax rate). Realize that the 5% turnover of the ETF did transfer away from capital gains to dividend income, but because the percentage is so low, the investor didn’t realize a considerably higher amount of taxable dividend income compared to the mutual fund. We’ll tie all this confusing dividend and capital gain taxability together next.

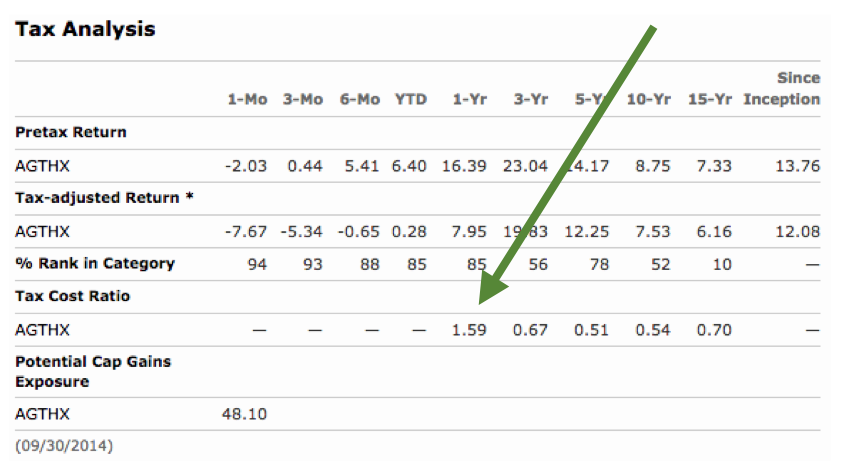

Another way you can measure how tax (in)efficient a fund is with a metric called the tax cost ratio. Morningstar currently makes this available, and it’s free. Just type in the fund name or ticker symbol on their website, then click the “Tax” tab. Here’s a screenshot.

Sometimes I pick on the Growth Fund of America because my wife and I owned it for years without questioning tax efficiency. In the summary above, you can see the fund had a 1 year tax ratio of 1.59. This means that on average, over the last year an investor paying 15% capital gains taxes would have lost 1.59% of their return to taxes! For example, if your mutual fund returned 10% last year and have a tax cost ratio of 1.59%, then your real return after taxes was actually 8.41%. Using the same ETF (IVV) as a comparison, it has a tax cost ratio of 0.45%. Clearly, the ETF investment structure proved advantageous by over 1% to the investor. 1% over time can add up!

The bottom line here is risk, return, and cost are all important factors when selecting an investment, but as we’ve seen it isn’t wise to disregard the tax cost of a mutual fund in a taxable account. If you have a taxable account full of actively managed funds, please don’t just go sell all of them and buy ETFs without doing a bit of homework. There are several assumptions built into my scenarios above, so check your tax records for your cost basis or check in with your tax advisor to see what the impact of selling your funds would be. You may find it’s worth it to spread out the sells over a few years so you don’t feel blown up with capital gains. Everyone’s investment and tax scenarios are different, and most likely not exactly the same as the hypothetical investor above. If you’d like me to help you better understand your specific situation, please leave a comment or visit the Contact page of my firm’s website.

Leave a Reply